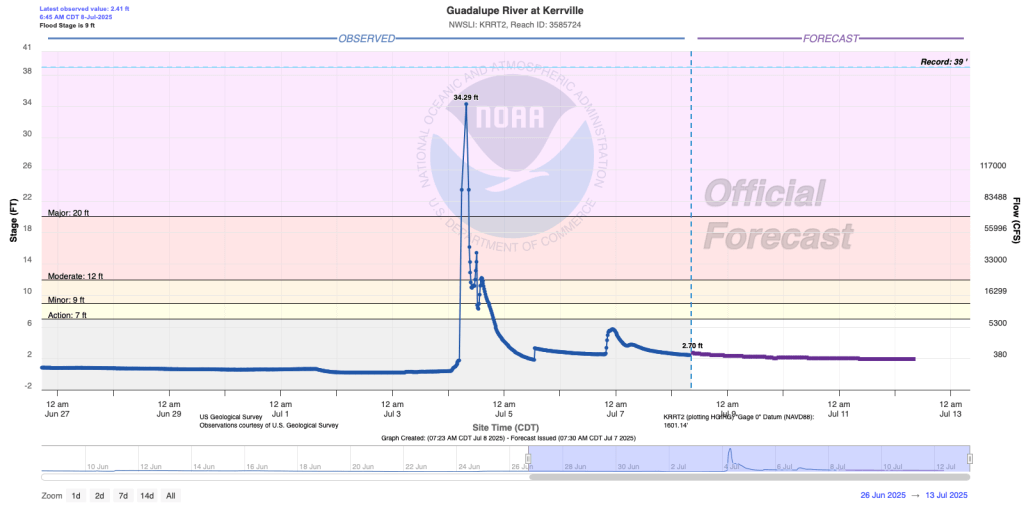

On the morning of July 4th, 2025, as citizens across the United States woke up for a day of celebration, residents in Central Texas woke up to a nightmare. This Independence Day will be remembered not for the celebration of America’s freedom and history, but the catastrophic flooding from the Guadalupe River that changed the landscape of Kerr County, Texas and the lives of its residents.

In this detailed event overview, we’ll break down why the flooding that decimated Kerr County, TX and killed at least 96 people in that county alone, including 36 children – was truly a perfect storm of elements to create such a catastrophic event.

—

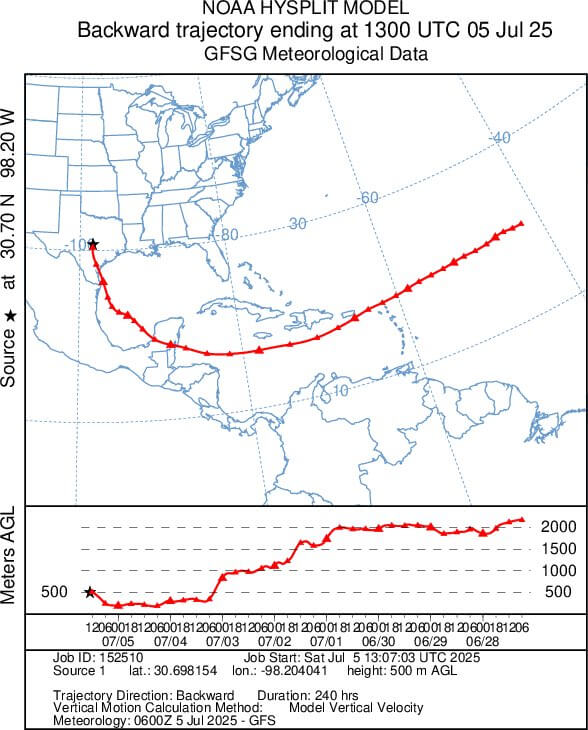

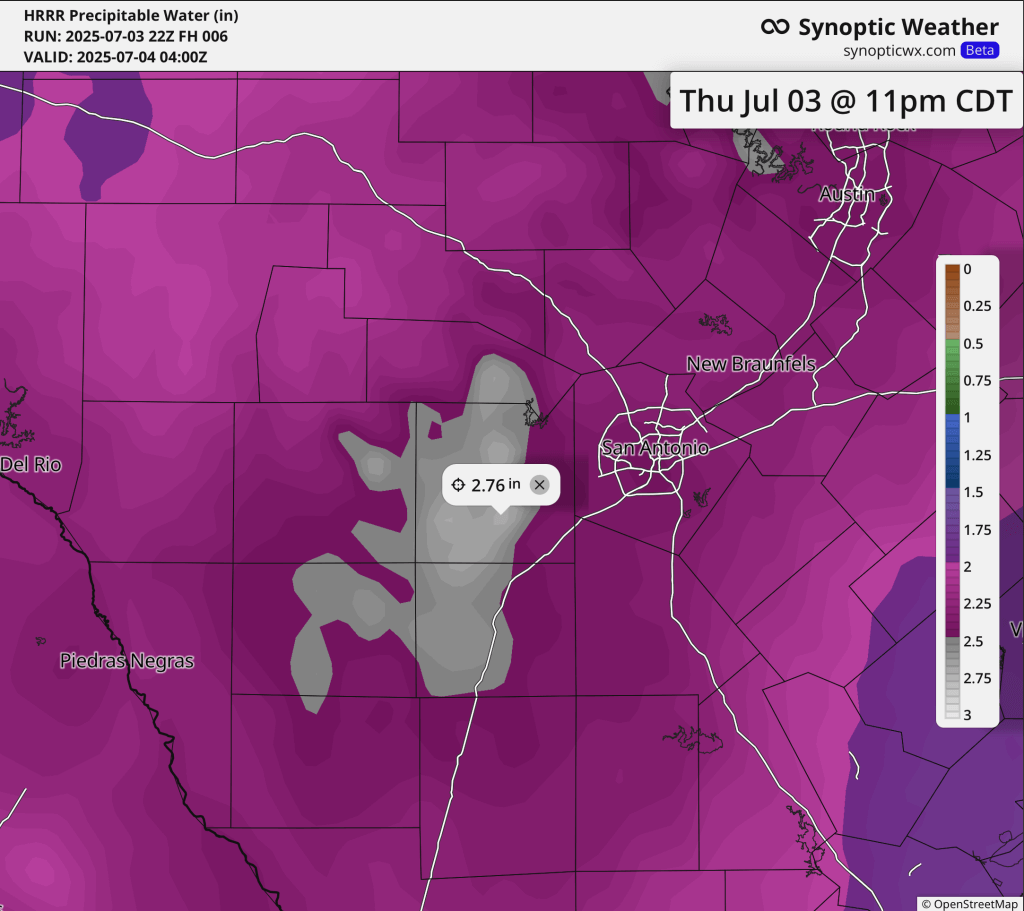

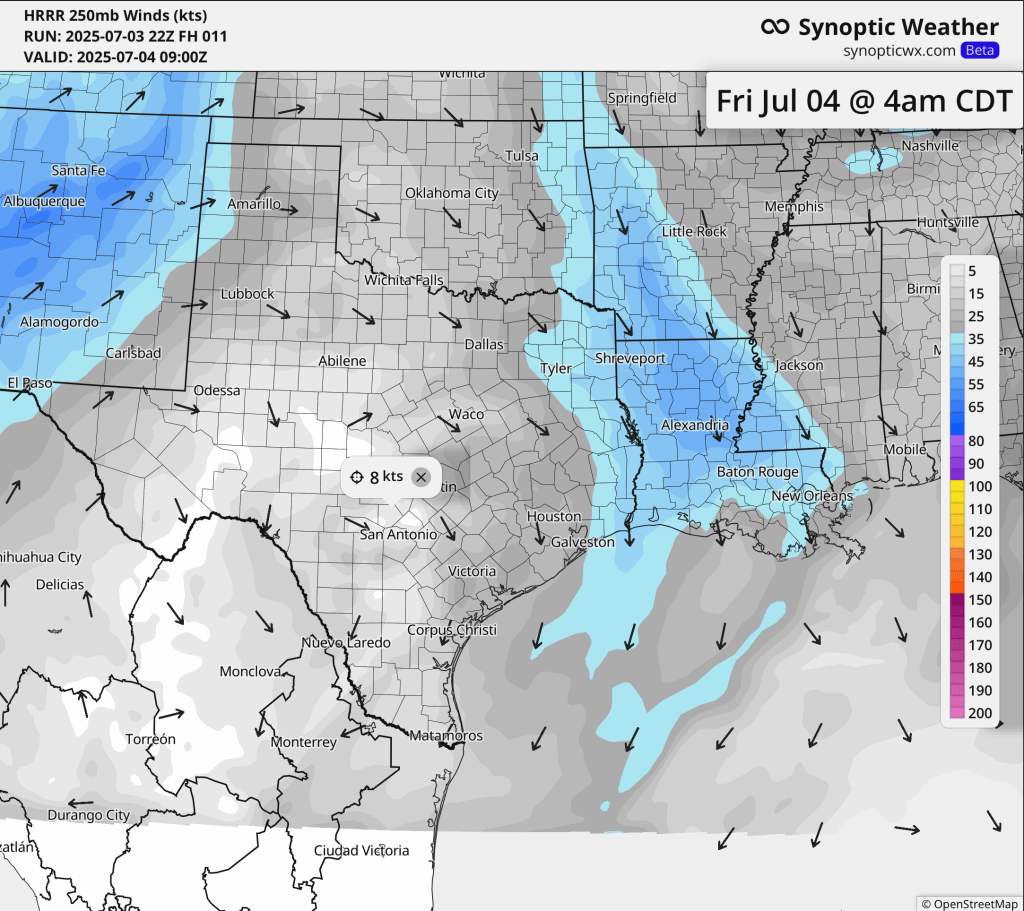

The ingredients needed to create extreme rain events include extremely high amounts of atmospheric moisture content, some combination of a stationary frontal boundary, weak steering winds or parallel winds promoting “training” of storms, instability to sustain storms and lift create persisting rising air.

With these ingredients in place, the environment was ripe for flash flooding for Texas Hill Country. The question was less about if and more about where excessive rains would set up.

This is where challenges and limitations within the science of meteorology come into play. While model data may at times be able to recognize and depict extreme rain totals in these types of set-ups, it remains nearly impossible to nail down the PRECISE location of such an event until it’s actively ongoing. In this particular case, a few model runs from the evening high-resolution, rapid refresh model depicted upwards of 20″ of rain and rainfall rates over 4″/hour near or in Kerr County, TX where the worst flooding occurred. However, it is worth noting that not every run of this particular model was so aggressive in highlighting the extreme nature of this event. This also highlights that while models may at times pick up on extreme rain events, it’s nearly impossible for them to pick out the precise location this type of rain will occur. In this particular case, even a small difference in the placement of the heaviest rain would have major a substantial difference in the outcome.

Why was the placement so key in this particular situation to determine the ultimate severity of the flash flooding? A few additional key factors that led to the extreme nature of the flooding on the Guadalupe River in Kerr County, TX included extreme drought conditions present in the area and geography.

First, and perhaps most importantly to the speed at which the river rose, were the drought conditions. When extreme rainfall rates combine with extreme drought conditions, the risk increases substantially for runoff and subsequent rapidly rising streams, rivers and flood zones. Drought affected areas have dense, compacted soil that prevents absorption cueing runoff instead of infiltration. As of July 3, Kerr County, TX was included under extreme (D3) to exception (D4) drought conditions – the two highest intensity values. The lack of ability for the soil to absorb the heavy rain rates meant that much of the rain falling would run right off into streams and rivers – like the Guadalupe. Had the excessive rains set up a few counties away in slightly lesser drought conditions – the outcome might not have been as extreme.

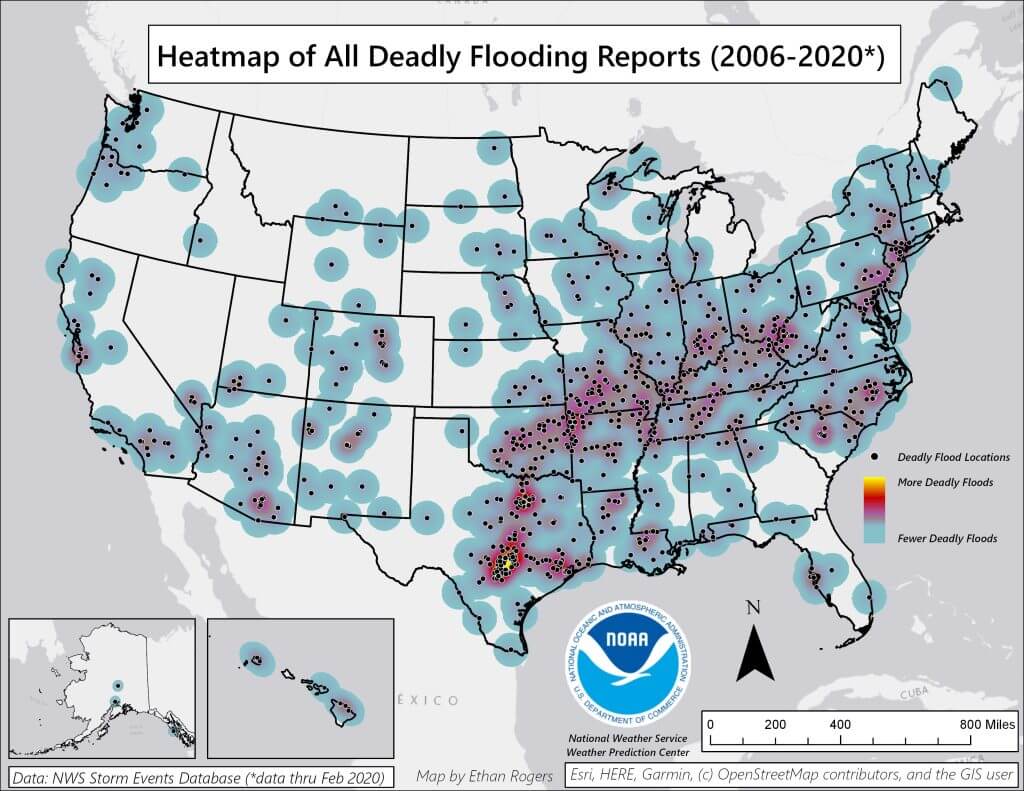

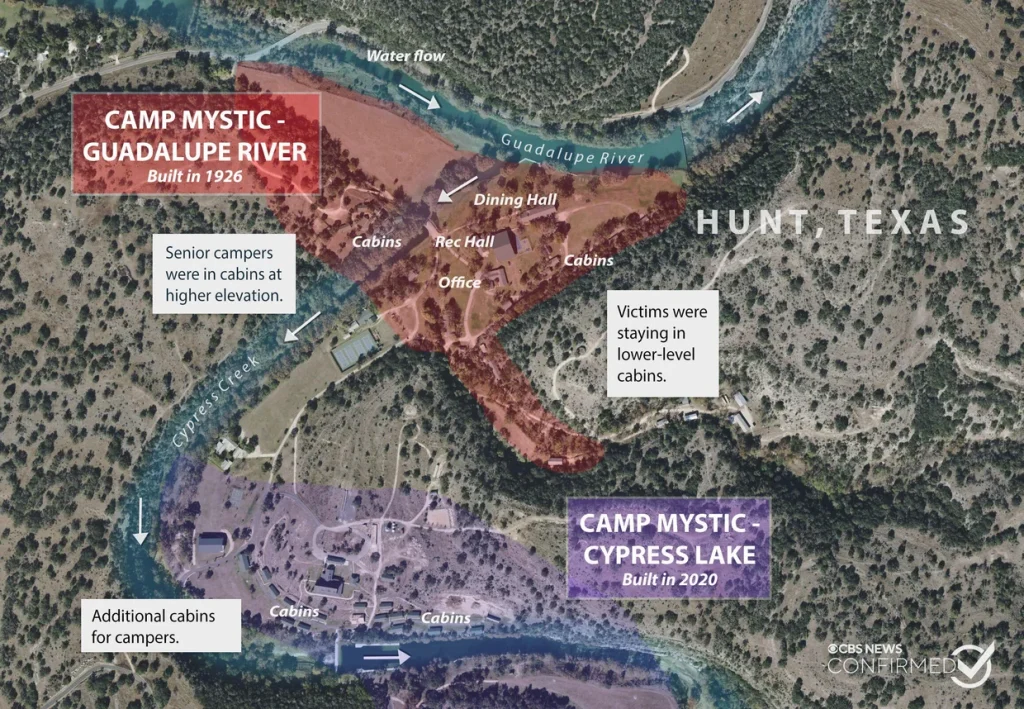

To make matters worse, the affected region sits in what is considered “Flash Flood Alley” – the most flash-flood prone region in the United States. This basin is one of the most dangerous spots in the United States for flash floods. In fact, less than a month ago, flash flooding killed 11 people in the San Antonio area. In particular, the Guadalupe River’s flow can be extreme – as it is regulated by a dam and the combination of geography and geology funnels rain into the river. The image below highlights the flow of the river and Camp Mystic – the site of the girls camp which was ravaged by the flooding.

When you combine all of these elements together, we end up with a catastrophe.

Societal Response and Moving Forward

This type of event – with all of the small nuances that impact the outcome, will naturally present communication challenges from forecasters to the public. Consider summer-time pop up thunderstorms – you can have a huge variety of outcomes in a small area where many stay completely dry and a few spots pick up multiple inches of rain. This event was similar, in that only 60 miles separated less than 1” of rain and 20” of rain and simply put, weather model data is just not advanced enough – and probably never will be – to nail it down to the precise spot. In fact, the model highlighted above was probably as skilled as possible in this type of scenario.

Then, this is a question not of forecast skill, but of the mindset of society in general. On potential tornado outbreak days, schools might shut down, athletics will cancel and under any tornado warning residents flock to shelter. Yet, what is the response for a flash flood watch or even a warning? The danger is real with both situations but the real probability of being directly hit by a tornado or a flash flood in any given storm is still relatively low in most cases. The question moving forward needs to be focused not on where to throw blame as some have chosen to do – but on how we as an industry can better emphasize the urgency needed to be placed on Flash Flood situations. Every person – like they do with tornadoes – should know whether they are in flood prone areas – they should understand when and how to heed critical flash flood alerts and we should continue to emphasize the risks of driving during flood warnings and through flooded areas.

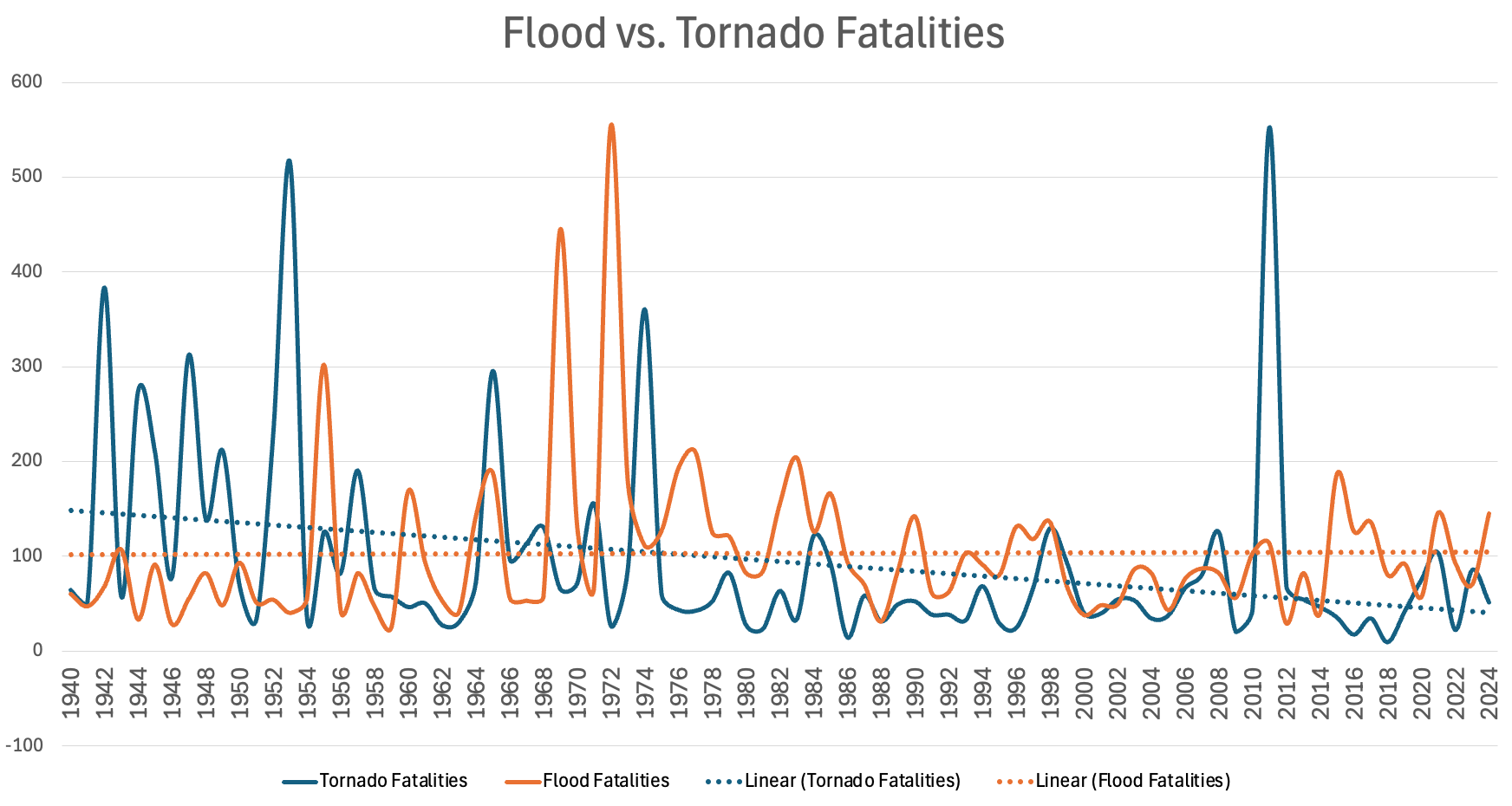

Over time, the efforts to educate, improve forecast skill and enhance safety related to tornadoes have shown an impact – with a general downward trend in tornado fatalities over the last century. Meanwhile, flooding fatalities have remained steady over the past several decades.

Rather than allowing justified anger and frustration prevent us from productive conversations to enhance the safety and understanding of these weather events, we should use it as motivation to do whatever we can to help and save more people moving forward. Flooding is the second biggest weather related killer in the United States – it is past time that we put a greater emphasis on that for the public. Not through fear or click-bait, but through thoughtful and productive discussions, debate, education and innovation. At BAM Weather, we are dedicated to doing that through increased 1 on 1 communication with users, more advanced insights and alerting and more education efforts on the dangers and facts of flash flooding events like this tragedy.