“Storms always fall apart around the city.”

“The lake protects us from tornadoes.”

“We never end up getting anything here.”

These types of phrases are said daily across the United States to explain why weather might not end up impacting a person’s particular location. Recent weather related tragedies have spawned widespread conspiracies, distrust in weather forecasts and blame thrown all around. Mother nature is one of life’s big mysteries for those that don’t live the science of it day in and day out. For those that don’t completely comprehend the dynamic processes that drive such a huge impact on each and every person’s life, sometimes a story – with or without scientific backing – is created.

“When we don’t understand something, we invent a story — we give it a name and make it familiar.”

— Yuval Noah Harari (in Sapiens)

In an era of social media weather misinformation, it’s so critical for experts in the weather industry to educate and adequately communicate life saving weather information. We must fight the desensitization of weather alerts from wild conspiracies to false alarms to outdated practices.

Solving the Desensitization of Severe Weather Information:

False Alarms

False alarms are part of weather forecasting. As an imperfect science, overwarning should always be a more common practice than underwarning and potentially causing people to miss life-saving information. However, for the everyday consumer, consistently getting warned for severe weather that never causes substantial impacts or damage to their location can lead to a loss of trust and perhaps even causing them to ignore warnings altogether.

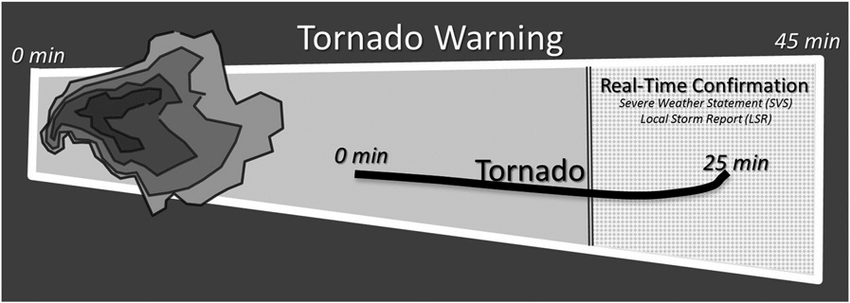

While improvements can be made in the warning process (more on this later), it’s important to understand why “false alarms” happen. Within any particular tornado warning polygon, only a very small path will actually be impacted by a possible tornado (most tornadoes only have a 50-100 yard width). Due to the nature of storms and tornadoes – the track can shift by several miles in a relatively short amount of time. For this reason, polygon areas are larger to leave room for potential error and ensure everyone within a reasonable distance is prepared for potential impacts.

However, while education is certainly part of this problem, outdated warning issuance practices have also left the public vulnerable to desensitization. Following changes to the county based warning system to the current polygon warning practice by the National Weather Service in 2007, warning areas shrunk, leading to less false alarms. However, even with advancements in technology and general understanding of tornadic supercells, little progress has been made since then to narrow warning areas further. A greater emphasis should be placed on fine tuning the warning areas and making advancements in storm propagation prediction technology. Some progress began with the Warn-On-Forecast project from the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL), but this has not yet reflected onto real-time forecasting technology.

In the meantime, BAM Weather is making a conscious effort with any kind of custom alerts to only warn areas where it is absolutely necessary. For the industry as a whole, it’s important we speak out and encourage efforts to shrink the polygon in an effort to limit false alarms and desensitization.

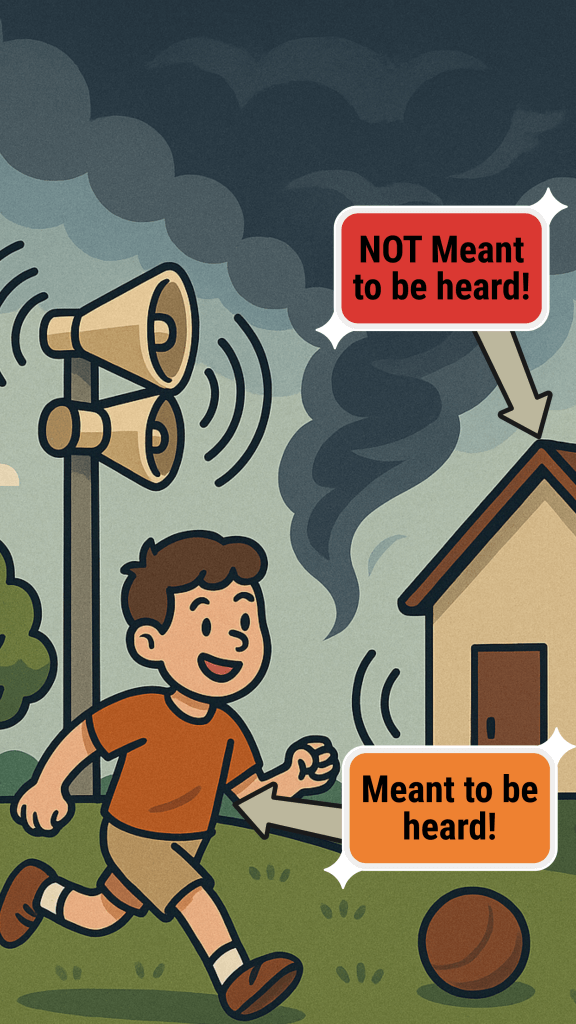

Tornado Sirens

Another major contributor to warning desensitization are tornado sirens. While sirens are used with the best of intentions, the lack of any national standard for when sirens are sounded cause consistent confusion during severe weather scenarios.

Examples of when sirens sound include:

- Areas under a tornado warning.

- An entire county if a tornado warning is touching any part of the county.

- A severe thunderstorm warning during a tornado watch.

- Funnel clouds reported by local law enforcement or spotters.

- Wind gusts of 70 MPH

- Hail larger than 1.5″

- Other non-weather outdoor emergencies

The variety of situations in which different counties sound tornado sirens causes unnecessary panic and confusion. When ultimately a siren is sounded for people not under a tornado warning – it causes people to ignore sirens and distrust warnings.

At the end of the day, until sirens are standardized and utilized for the same situation every time, they should not be relied on as an accurate source for warnings (and they were never made for indoor use in the first place). It is critical to have another, accurate source of alerts like the Clarity Weather app.

Flash Flooding

Similar to tornadoes, dangerous flash flooding most often does not affect the entire warning polygon – but rather flood prone areas and roadways. Rather than ignoring warnings altogether, the weather industry needs to make a concerted effort to educate the public on the common impacts associated with Flash Flood Warnings.

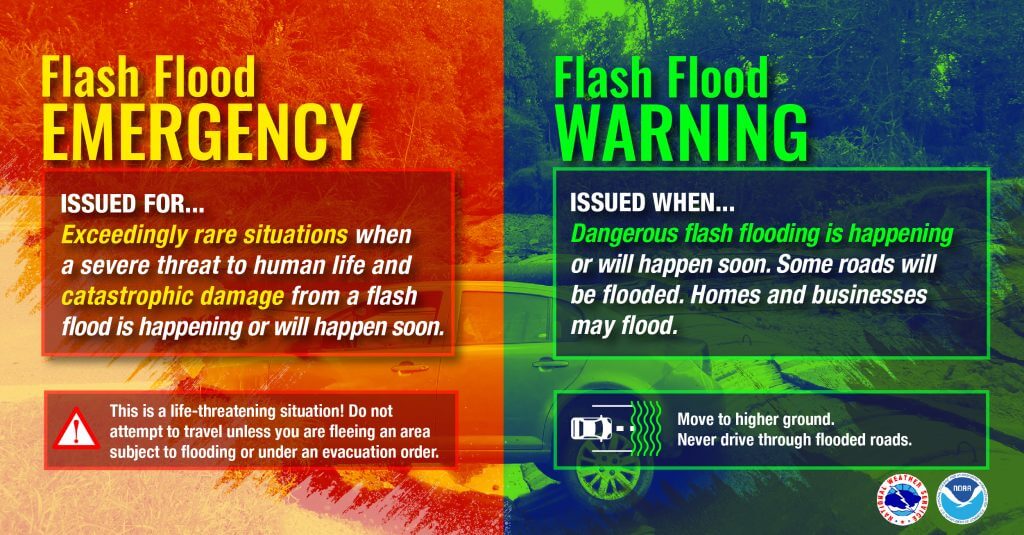

It’s also critical to highlight the difference between Flash Flood Warnings and Flash Flood EMERGENCIES (like what Kerr County, TX was placed under during catastrophic flooding earlier this month). Flash Flood Emergency Warnings are for catastrophic floods that pose an extreme threat to human life and property. In these situations, evacuating and/or moving to high ground is absolutely necessary. Doing a better job at differentiating warning notifications and the colors/pattern of these warnings on maps may help to highlight the different dangers associated with these different levels of flood warnings and produce more urgency in both situations.

It’s also critical to highlight the difference between Flash Flood Warnings and Flash Flood EMERGENCIES (like what Kerr County, TX was placed under during catastrophic flooding earlier this month). Flash Flood Emergency Warnings are for catastrophic floods that pose an extreme threat to human life and property. In these situations, evacuating and/or moving to high ground is absolutely necessary. Doing a better job at differentiating warning notifications and the colors/pattern of these warnings on maps may help to highlight the different dangers associated with these different levels of flood warnings and produce more urgency in both situations.

Regardless, Flash Flood Warnings MUST be taken more seriously and that needs to be emphasized. Travel should be limited as much as possible during these warnings – as 80% of flooding fatalities occur from driving or walking in flooded waters. Flooding remains the #2 cause of weather related fatalities in the United States behind only heat.

These three factors are things that can be easily mitigated with enough time and effort – and it would likely save lives. A 2017 University of Nebraska study highlighted that nearly 40% of students chose not to seek shelter in two-thirds of all warnings they experienced. This is a staggering statistic that highlights the progress that still needs to be made in severe weather communication and urgency and why these conversations are so critical for the safety of the general public. As an industry we cannot be complacent – we must act with urgency and intention and use our knowledge and platforms to touch as many people as possible with what could ultimately be life saving education.